Intro/Outro (00:12):

Good morning, Scott Luton here with you on this edition of this week in business history. Welcome to today’s show on this program, which is part of the supply chain. Now family of programming. We take a look back at the upcoming week, and then we share some of the most relevant events and milestones from years past, of course, mostly business focused with a little dab global supply chain. And occasionally we might just throw in a good story outside of our primary realm. So I invite you to join me on this. Look back in history, to identify some of the most significant leaders, companies innovations, and perhaps lessons learned in our collective business journey. Now let’s dive in to this week in business history.

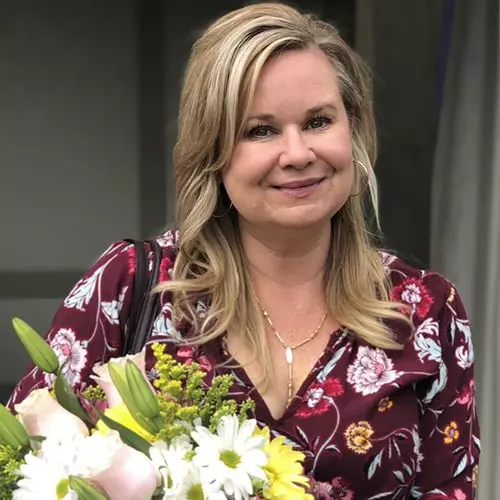

Kelly Barner (01:11):

If you look at gourmet kitchens today, you will almost always see a sleek gas range. And yet there was a time that quote unquote modern kitchens were moving away from open fire, not towards it. Home cooking in the late 19th century was a messy business, usually conducted in tight quarters, even in the largest homes, there was likely to be a sink, a work surface of some kind and a stove, probably one that was fueled by wood. The quality of the food and even its contents were suspect as well. Pretty much ensuring that no one considered cooking a hobby or the kitchen, their happy place, keeping the cook surface and oven running at a consistent temperature was a challenge and let’s face it. It probably didn’t happen often not to mention the effort required women to keep a source of fuel at hand replenishing it, as it was used up spring cleaning was an absolute necessity.

Kelly Barner (02:18):

Back then, as every surface inside a home would be covered in. So, and Ash from the fire and stove that had to be kept running all winter. And then in the 1880s came a wave of change that would alter the way everything in homes worked slowly at first, and then it spread quickly. What was that change? Household electrification as electricity worked its way from cities into rural areas and from wealthy households out to the general population, nearly everything inside the average home changed. That includes the business history moment. We will mark today, the patenting of the first electric stove. I’m Kelly Barner your host for this episode of this week in business history on supply chain. Now I love history. Everything we do in business today stands on the shoulders of the great thinkers and innovators that came before us, whether we realize it or not.

Kelly Barner (03:29):

And even the most mundane objects in our lives have a history, all their own. The more familiar we are with those items, the less likely we are to stop and think about how they came to be and who designed and built them. If you enjoy the unique blend of storytelling and business history that Scott Luton and I share on this week in business history, please take a minute to subscribe to the podcast and share a review that will help others find us. And now back to this week’s business history story, if you’ve ever been to Walt Disney world, you may have ridden the carousel of progress originally created for the 1964 New York. World’s fair. The carousel of progress tracks one imaginary family from the 19 hundreds to the 1920s, the 1940s, and finally the 21st century. The scenario remains largely the same, but all of the technology changes and the family changes with it.

Kelly Barner (04:38):

I love that ride, which probably comes as no surprise given my affinity for history. And I don’t think it is a coincidence that in each stage of time we see the family in their kitchen. That is where most home innovations live on June 30th, 1896, William S Hadaway earned a patent for the first electric stove. Other related patents had been awarded previously, but they were for more general heating devices, not necessarily dedicated to cooking for instance, on September 20th, 1859, George B. Simpson received a patent for an electro heater surface heated by a platinum wire coil empowered by batteries. He described it as useful to quote warm rooms, boil water and cooks. Hmm. Then in 1892 Canadian inventor, Thomas a Hern filed a patent for an electric oven. And if you’re interested in why that patent didn’t preempt Hadaway from being awarded one in the United States four years later, listen to my recent episode of dial P for on the world trade organization and intellectual property protections.

Kelly Barner (06:03):

I’m sure there were differences between the two designs, but patents and trademarks are legally confined to the country. They are issued by only extended internationally through trade agreements. Now we don’t know much about headway’s personal life, but we do know he was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and worked as a scientist and an inventor. In fact, his inventor credits don’t end with the electric stove, but they do remain in the kitchen. He eventually took a job with the Westinghouse electric company and while he was there, he designed the first toaster oven in 1920. Well, today we call it a toaster oven. At the time he described it as a horizontal combination. Toaster cooker clearly Hadaway did not do a rotation through marketing at Westinghouse. The idea was an accident like most good ideas. He was actually just playing around with the materials left over from manufacturing, more traditional electric stoves.

Kelly Barner (07:12):

As with any new invention. There were issues with those early electric stoves and toaster ovens. They weren’t much better at regulating temperature. The cost of the electricity was sky high when you compared it with gas and wood and the heating elements burned out quickly. But the appliance showed promise and improvements continued to be made by the 1930s. They were found in far more homes, both because consumers trusted them. And because the cost of electricity had come down substantially making them more affordable to operate. As I was researching the details around these early electric stoves, I kept coming back to information that indicates what a unique time in what we call domestic engineering or domestic science. The late 19th century was there were many other inventions and changes in public thinking that came together between about 1890 and 1910 at the Chicago. World’s fair in 1893, the same year Hadaway earned his patent for the stove.

Kelly Barner (08:24):

Another now common kitchen appliance took the top prize for best invention. The dishwasher at the time, the dishwasher was positioned as a commercial appliance, really only fit for hotels and restaurants, but we all know how that story ends. It was starting on a path that would have dishwashers appear in most people’s homes. The typical kitchen was taking a leap forward in terms of what was possible, partially because of innovation, manufacturing, and electricity. And partially because the world’s mindset about food and cooking was changing. The industrial revolution, which is typically regarded as having ended in 1840 was starting to spill into people’s homes. The second industrial revolution, which stretched from 1870 to 1914 was all about manufacturing, mass production and standardization. In addition, people were starting to raise their cleanliness standards, especially in home kitchens. And the same ideas were starting to percolate about food itself.

Kelly Barner (09:41):

Additives were routinely included in food to make it cheap and shelf stable. Unfortunately, there was no expectation that it needed to be proven safe for consumption before it was put on the shelf. If that seems like an archaic way of doing things, consider this, it wasn’t until 1966, that the U S D a mandated ingredient lists to be added to food packaging. And even then the rule only applied to goods being sold across state lines. So back in the 1890s, you had absolutely no idea what you were consuming. It was scary, but change was on the horizon in 1902, the agriculture department’s chief chemist, Dr. Harvey, Washington Wiley assembled what he called his hygienic table trials. Of course, that name wasn’t selling any newspapers. So George Rothwell brown, a reporter at the Washington post came up with a better name. The poison squad, an otherwise healthy group of young men would sit down to delicious meals that were laced with varying amounts of everything from borax to formaldehyde.

Kelly Barner (11:06):

Then they were carefully studied to see the effects on their bodies over time. The results of this unusual study were presented to Congress and in 1906, they led to the passage of the meat inspection act and the pure food and drug act. The first federal laws aimed at food regulation. So we have safety covered, but what else was going on in the last years of the 19th century, people were learning to cook and it wasn’t just to keep their families fed. The kitchen had finally become a pleasant enough place for cooking to bring joy and for it to allow women primarily to show off their culinary skills in the same year that Hadaway got his patent for the electric stove, little brown and company published the Boston cooking school cookbook written by Fannie farmer. Fannie was a trained cook during the height of the domestic science movement, clearly inspired by the second industrial revolution.

Kelly Barner (12:14):

Domestic science was the purposeful study of skills used in the home cooking, cleaning, sewing, et cetera. These skills had always been passed from generation to generation, but now they were being swept up by the same desire for standardization that was playing out in factories. Fannie farmer is known as the mother of level measurements before her and her cookbook recipes might say things like include a pot of butter about the size of an egg or pour in a TEAC’s worth of milk. These were completely nonstandard measurements and the impact showed up in the results. Fannie replaced those descriptions with the standard cups, teaspoons and tablespoons we use today. And if you’ve ever tried to learn a recipe from a family member that knows a recipe so well, they use the, I don’t know about this much system of measurement. I’m sure you’ll be able to appreciate Fannie’s contributions.

Kelly Barner (13:24):

Not only did she provide clear explanations and standardized ingredient measurements, but she also taught cleanliness and emphasize that food should look appetizing. In addition to being nutritious and tasting good Fannie completely understood that food was at the core of good health. She went on to open her own school. Miss farmer’s school of cookery in 1902, during her lifetime, over 4 million copies of her book were sold a title that the publisher had. So little confidence in that they were only willing to print 3000 copies in the first run kitchen technology continues to evolve. And even though magazine kitchens usually have gas stoves in them often with very brightly colored knobs, proponents of electric stoves still exist. For instance, gas stoves waste more energy than electric. Only 40% of the energy used by a gas stove is transferred to the food compared to 74% with electric. And now they both have to compete with induction cooktops, at least from an energy efficiency perspective, they transfer up to 90% of energy to the food with so much living going on in our kitchens. Innovation is bound to continue. Just don’t forget to notice it. And of course, remember where it came from

Kelly Barner (15:05):

On that note. It is time to wrap up this addition of this week in business history. Thank you so much for tuning into the show each week. Don’t forget to check out the wide variety of industry thought leadership available@supplychainnow.com. As a friendly reminder, you can find this week in business history, wherever you get your podcast from and be sure to tell us what you think we would love to earn your review. And we encourage you to subscribe so that you never miss an episode on behalf of the entire team here at this weekend, business history and supply chain. Now this is Kelly Barner wishing you all, nothing but the best. We’ll see you here next time on this week in business history,