Intro/Outro (00:02):

Welcome to Veteran Voices where we amplify the stories of those who’ve served in the US Armed Forces. Presented by Supply chain now and the Guam Human Rights Initiative, we dive deep into the journeys of veterans and their advocates, exploring their insights, challenges, impact, and the vital issues facing veterans and their families. Here’s your host, US Army veteran, Mary Kate Saliva.

Mary Kate Soliva (00:33):

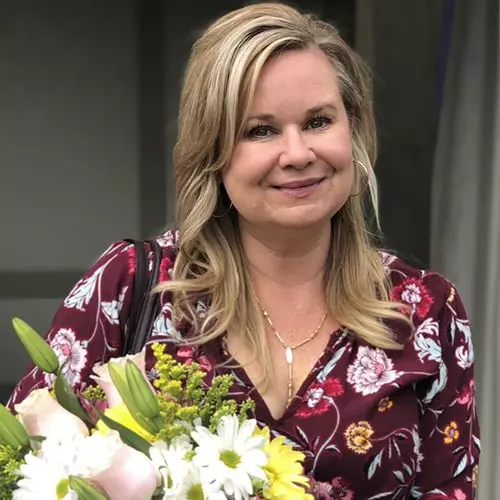

Hello everyone. Thank you for joining us here today on Veteran Voices. I’m your host, Mary Kate Saliva Army veteran, and I’m really excited to have you join us today. And for those of you who are tuning back in, welcome back. Veteran Voices is a podcast as part of the supply chain now family of podcasts, and you can get it wherever you get your podcasts from. Veteran Voices focuses on interviewing veterans who are serving beyond the uniform, and I’m super honored and very honored to have our special guest today, Dr. Amy Stevens. And she is a Navy veteran and I’m just so thrilled that you’re here. Thank you, Amy.

Amy Stevens (01:12):

Thank you for having me.

Mary Kate Soliva (01:14):

Yes, and I am glad that we had a chance to speak earlier and that we got connected in the great state of Georgia. I’d love to kick off our episode as I usually do with some motivation, and you are welcome to sing or I know you mentioned Navy doesn’t do the cadence thing, but if you’d like to provide us with your favorite motivational quote, I’d love to hear it.

Amy Stevens (01:40):

No, Jody’s in the Navy, very rare we leave that to other people, so it’s fine. You said motivational quote and so it was kind of hard to know because sometimes I’ll say live large, live well known. Some people get way up there, but it reminded me of something that actually I’ve had on my wall for a long time, so I brought the proof. Oh, great. It’s a very simple quote, but I actually came up with this a very long time ago, and it’s from the Bible actually, Ecclesiastes four six, and the translation in common language would be better. One handful with tranquility than two with toil and chasing after the wind.

Mary Kate Soliva (02:22):

Oh, that’s

Amy Stevens (02:22):

Beautiful. Is that different? It’s

Mary Kate Soliva (02:25):

Very different.

Amy Stevens (02:28):

I’d rather have peace than strive for something and have conflict is that I take care of business. No doubt. Right. But why fight if you don’t have to and if you can make positivity happen in a tranquil way, why not? And so I’ve actually kept on my wall for a very long time, so I just thought I’d share that one.

Mary Kate Soliva (02:51):

No, I thank you for sharing that and that’s a beautiful verse. And which chapter did you say that was from? I’m going to have to check

Amy Stevens (03:01):

Four six. I don’t remember. I must’ve been in a bible study at that and we’re talking almost 30 years ago that I came up with that. It was actually in my office when I worked for the US Department of Labor in the 1990s. I had that up there and then that’s when I just never threw away. I thought it was very meaningful.

Mary Kate Soliva (03:20):

Well, the fact that it still rings true today, I think that says something. I know we’re going to be going in later about you being the founder of the Georgia Military Women, and I’m excited to talk about that in a bit. But I’m going to take us a little bit back to your upbringing where you grew up and I think it tells a lot about person and just not forgetting where our roots are. So I’d love if you could share about where you grew up in a little bit of anecdotes from that time.

Amy Stevens (03:49):

Oh, I don’t know about anecdotes. I don’t mind saying I’m 70 years old. I grew up in Augusta, Maine. That’s where I’m from is that you probably have not met too many native Mainers. We’re very proud of that. So although my roots have gotten a little tangled, I am the gypsy of the family, everybody else. And for whatever reason, I guess I’m the chosen one that I decided that there was something else outside of the borders of the state. And I’ve been on the go ever since I was a child. I’m the one that always did that. Even though I like tranquility and I love Maine, it is my home. And someday, maybe I’ll live there more, but is it, there’s something that was a calling to leave and it really started right from the beginning that I just had this sense of adventure and wanting to try new things.

(04:39):

I’ve always been interested in other cultures and I was the first person in my family to go to college. So a low income family had a struggle. I was inspired to go to college because my cousin, Lila Stevens was a army nurse. She served in Vietnam, did multiple tours there. And I used to remember her coming home. She was quite a bit older than me, and she’d come home with her big Labrador dogs and sometimes she’d bring a friend and just hear about what she was doing. Of course, she didn’t tell us the bad stuff. It was more of the adventurous stuff that I thought I wanted to become a nurse just like her. And I actually did start college for nursing and didn’t take long for biochemistry and I to decide that that was not a good match, you

Mary Kate Soliva (05:30):

And me both.

Amy Stevens (05:32):

And so I actually became a broadcasting major. It’s kind of bizarre, but I actually totally switched. I tried theater, figured out that four 11 ladies don’t usually get the leading lady role. So I became a broadcaster and I ended up actually switched to what was then known as Lynchburg Baptist College. I felt a calling from God to be at a school that was Faith-based and graduated from there in 75. Ended up working in the broadcasting area, and I ended up actually working in educational television and relocated to, I actually, I lived several years in Milwaukee from the state of Maine. And then back then women weren’t that much in broadcasting even.

Mary Kate Soliva (06:21):

That’s what I was going to say. It’s like

Amy Stevens (06:24):

Thing

Mary Kate Soliva (06:25):

Right.

Amy Stevens (06:26):

As though I kind of struggled with finding my place and again, keep mind. I’m a very short person, and so I probably looked like I was 10 or 12 by the time

Mary Kate Soliva (06:36):

You keep saying that. I know. To me it seemed very tall, but I know you keep saying

Amy Stevens (06:40):

Short. Yeah, but I really was, and one of the things that kind of kept nudging me was Lila and how she had done all of her stuff. And at a certain point in Milwaukee, I said, if I don’t do it now, I’m not going to do it at age 25, which is kind of old, I ended up joining the Navy to be a abroad. Yeah, that’s how I started out. I went to OCS at Newport, Rhode Island. My first duty station was Adak Alaska, which people always think is interesting because it’s this tiny little island out in the Tians that’s closer to Russia than it is to the mainland. And after that, I went to Japan for a couple of years, traveled all over the Far East, was in and out of particularly Korea during that time with,

Mary Kate Soliva (07:28):

Because I remember you mentioned that about the time. I am curious though, about why you chose the Navy. I know you said 25 and to me, 25 is still young, but I’m curious as far as the other branches go, what was so appealing about the Navy? And I’ve had some guests say that they saw some, the message on the billboard and it spoke to them or that commercial.

Amy Stevens (07:50):

I’ll tell you. Okay. The reason why I didn’t join the Army was because I ran out of money in college and I went down to, actually, I almost joined the Army when I was still in college, but the Army recruiter lied to me.

Mary Kate Soliva (08:01):

No way.

Amy Stevens (08:02):

That’s what it was. The army recruiter lied,

Mary Kate Soliva (08:04):

Stay on them.

Amy Stevens (08:05):

It was a trust thing, as I figured is that they misled me on what I was signing up for. Unfortunately, I figured out a way to pay for my college and got out of that one. So I’m glad that that did not happen. That was in 73. And then when I decided, because I decided the army was out because my trust was broken, I actually talked to the Air Force guys and that’s where I thought I wanted to go. But actually what happened with the Air Force recruiter, now I had my degree and everything was going to go in as an officer. The guy was just hitting on me. He was all about how pretty I was and how great I’d look in the uniform and all of that kind of stuff. So that’s how come I went down the hall to the Navy. I mean, that’s kind of what happened is that I knew I wanted to join the military as far as the Marines, no offense to my Sea Service sisters, I guess there must not have been a Marine recruiter on the hallway.

(09:05):

It ended up being the Navy. And of course I really did not know what I was getting myself into. The Navy had just changed, by the way, at that point in time, 1978 is the last year that the Navy had what we call the waves women activated volunteer service. The Army had the wax, the Women’s Army Corps, that ended in 78. And so when I joined up in January of 79 and reported to Rhode Island for OCS, it was the first co-ed classes that they had ever had. And we weren’t teams anymore. We were called Winds, women in Naval Service. But that acronym didn’t stay very long either. But that’s for, and they really were not prepared for females at all. So it was quite a different type of thing. And having men and women in the same company, all of that kind of stuff. So it was a big transition.

(10:04):

It was pretty clear that women were not really wanted in the Navy. We did some training where we’d go out for training cruises and things like that, and the chiefs would make it very clear that they did not want us on their ship. That was very clear. And at that time, only one woman per class was allowed as they had just started, that they would barely started having women go on support ships. So this would be like the Oilers and supply ships, never a combat ship, but the support ships, they had started putting enlisted and officer females on board, but only one per class. And actually they did offer, oh my

Mary Kate Soliva (10:46):

Goodness,

Amy Stevens (10:47):

They did offer me the opportunity for whatever reason, I don’t know. I am always one of those that said, well, if somebody else isn’t going to do it, maybe I should do it. So I was in a leadership position at OCS and I was offered a ship, and I had joined the Navy to be a broadcaster. So that’s how come I ended up actually going to ADAC as the broadcasting officer in a tiny little. Did

Mary Kate Soliva (11:11):

You have any of the mentors at that time? You said they didn’t know what to do with the women. I’m curious, did you end up having other brothers in arms helping you out? Was it the women sticking together? How was it during that time? Did you have mentors?

Amy Stevens (11:29):

There weren’t that many women to stick together, so you just didn’t see that.

Mary Kate Soliva (11:33):

So did anyone take you under their wing to help mentor guide you at that time?

Amy Stevens (11:38):

I would say not really. Is that actually, I don’t want to get too off into the harassment type of thing. The sexual harassment was part of the story. Every place I went is that there were people that would be nice to me, but there was the agenda. Nice. There definitely was that. But if you try hard to get along with people, I would always find my people, right, people that I could hang out with and do things. And actually I feel really blessed. That’s one thing I think most of us appreciate. And today I still have at least one friend from every duty station I was at, somebody that I can reach out to say, remember when we did X, Y, Z? And that’s very cool is that people know where you’ve been. And if I wanted to go back to Alaska, I’ve got a girlfriend up there that I could call up and say, Hey, can I come visit? They’ve got a guest room. Her husband wouldn’t mind me coming. So I could do that tomorrow. And I love that. Our friend from Japan lives down in Sarasota now, and she actually comes to visit me every summer. We have kind of this travel relationship is that she loves to travel. And so when I can, I think that’s

Mary Kate Soliva (12:52):

Fantastic.

Amy Stevens (12:55):

Is so important as part of the story of being in the military that we were talking about this the other day in my group about civilians have no idea where we’ve been. It’s a awkward conversations. And the military kind of puts a lot of other stuff beside all of our other reasons for being, they kind of come together and suddenly you realize, oh, you were in the Navy. Oh, I was in the Navy. And then we have this amazing conversation, whether it’s men or women that you meet. So I’ve always enjoyed that it’s part of who we are.

Mary Kate Soliva (13:27):

And I think that’s so true. And I always say that there’s never a, I can’t really go anywhere without having a couch to sleep on when it comes to the 50 states. And actually I could probably include the territories in that too, of just the incredible men and women I’ve met in service. But I did want to touch about, because it’s so fascinating for me, I’m still serving now. And the fact that the time that you served in the seventies and eighties and just thinking about that timeframe for women, how was that in the sense of resources and policies to protect you? You mentioned some of the harassments. Was there anywhere to go, anyone to talk to policies?

Amy Stevens (14:10):

None of that existed. So it’s like, I’ll admit there were token things, there were token things. I was one of the early ones. I know some other people that were even more involved in it, but definitely you were a target. There was always somebody approaching you and basically making comments if you wouldn’t go along with whatever. And

Mary Kate Soliva (14:34):

For mothers, for the service, women who ended up having children?

Amy Stevens (14:38):

No, no, I’m just saying harassment and things like that were just Part of it is that most of us were single women. There weren’t that many married women. If you got pregnant still, you tended to get out right away. They just had switched that. I don’t remember what year that you didn’t have to get out, but it was very difficult. So you had all of that. And actually I was one of the first ones after I did my tour in aec, my next duty station in Japan was human resource management detachment. And they did training on things like equal opportunity, drug and alcohol prevention, sexual harassment prevention, all of these soft touch HR types of things is I was what you called a general unrestricted line officer. Maybe. I think I told you about that previously. I should tell that story again. I think Yes, you

Mary Kate Soliva (15:28):

Should. I want to hear that acronym.

Amy Stevens (15:29):

Everybody should know about it. Okay, at OCS. Okay, here you are with all the guys and the Women and

Mary Kate Soliva (15:36):

Officer Candidate School. Yes.

Amy Stevens (15:38):

Officer Candidate school. Okay. So you’re there and you get to pick your specialty type of thing. And so you’ve got the submariners data, a submariner. I have stories about that, but I won’t tell them. Now, pilots went down to Pensacola. So we did not have pilots at OCS because we were up in Rhode Island and you had surface warfare and you had supply corps officers and you didn’t have medical people. They did a different training also. So you were a submariner or you were ships or you were supply or you were whatever else. And whatever else at the time was called general unrestricted line. So when we talked before, I had you do it and if anybody’s listened to it, I want you to write down the acronym, get a piece of paper and do it general unrestricted line officer. The first word, because we love acronyms, the first word is G, write that down. Un write down a U restricted. Write down an R line. Write that down.

Mary Kate Soliva (16:45):

Exactly. Girl,

Amy Stevens (16:47):

It spells girl.

Mary Kate Soliva (16:48):

I’m sure the guys love that.

Amy Stevens (16:50):

Well, and the thing is, is that so general unrestricted line officers have the same level of command accession. So if nobody’s senior is present to take charge, that’s what a line officer basically does in your specialty. But you take precedence over the restricted line and the medical people. So here I was a girl in the Navy, and what was really funny was that it took a couple of years, but what would happen if somebody was in a pilot or a ship driver or driving submarines and for some reason they washed out, they would become girls. So here we had guys becoming girls.

Mary Kate Soliva (17:33):

Oh no,

Amy Stevens (17:35):

Then, and so they changed that. I don’t know what they call it now. They’ve come up with some other little acronym to cover it. But basically the girl designation meant that we did a lot of different things. So as a broadcast worked online, I was a generalist, so I did that only for a year. But education and training really was my subspecialty. But you could have a subspecialty in things like human resources and some other things. So guys, I’m really

Mary Kate Soliva (18:04):

Curious what that guys becoming girls, and I can’t imagine the acronym last very long even now, but I’d love to hear about in broadcasting as far as what was a highlight for you as far as a story that you covered in your career in your military while you were in the military?

Amy Stevens (18:24):

Oh. Oh, no, honey. I was on an island in the middle of nowhere. We had like 5,000 people. They shipped in tapes that we could broadcast. We were on a secret squirrel location where the Marines would love to put us in the dirt. So all we did was play. We had two radio stations to entertain people and one television station that was pretty limited based on whatever at the time. Do you even know what VHS tapes are? Tapes. Okay.

Mary Kate Soliva (18:54):

The last version,

Amy Stevens (18:55):

They didn’t even have VH tapes and they had the two inch tapes and they would come on these big reels and we would

Mary Kate Soliva (19:01):

Only in the movies. I’ve seen those.

Amy Stevens (19:03):

Okay. In the dark ages. So that’s what we had, and we basically were a key part of morale on the island really is what that was. And we would do annual shows and things like that. I do have a lot of stories about adac. I guess one of the things was going swimming in the bearing sea with the Marines. Again, there were very few women, especially women officers on the island. So I of course was very popular present on a scale to one to 10, you’re always going to be a 10. The only one. So the Marines and I You’re

Mary Kate Soliva (19:41):

A hoo.

Amy Stevens (19:42):

Yeah, the Marines and I went swimming on Groundhogs Day. So February 2nd, 1980. I do have pictures to prove it. The Marines and I went swimming. It was like 32 degrees. They actually, they did have nurses on the island. The nurses and the ambulances and everything were pulled up to the edge of the water to make sure that if anybody had a heart attack or froze or something that they could pull us out. It was kind of fun. So I like

Mary Kate Soliva (20:10):

A risk assessment not taken. Yeah, no, I think that’s fantastic. I love your stories about that. So I’d like to take it to your transition. I know we could spend a lot of time talking about the whole military service, but I think it’s really important, especially for our listeners who may be going through transition. Now, you said at the time even policy, what policies, what resources? So I’m curious if there was anything for the transition process for you, what was that decision point for you to finally leave the Navy? You’ve got

Amy Stevens (20:43):

To realize that the military was in a transition at that time period. I’ll jump around, but on a more serious level, you have to think how much the military was changing as that we’d come out of Vietnam and all of that kind of stuff. The Cold War period, there was still war going on, and I do want to be serious about that. There were a lot of things going on that people don’t think about. So when you say pre nine 11, we still had a lot of people going in harm’s way, and that’s not always acknowledged. And I do want to show respect to those people that did that. We were also though, go through a cultural transformation because again, it used to be that women were partitioned over on the other side of the base, like wire fences and stuff. I’ve talked to some of my friends who are in their nineties that are veterans and say, oh, we never even talked to men because they kept us so security.

(21:31):

So there were a lot of issues. And that was how come I was one of the first HRM officers to be involved in integrating women into the services. And it really used to be one of the little hassles that I got involved in at one point was a unit that would not allow their women from their unit to date men from a different unit, for example. It was kind of like you own them. Yeah. I mean there was this kind of conflict. So there was always this little turmoil type of thing going on of ownership and traditional roles of women also during this time period were also changing. My follow on duty station actor Japan was I was a bootcamp division officer at RTC Orlando Recruit Training Command Orlando. Oh, interesting. Among other things, I am the proud at one point officer in charge of the swimming pool back in the water.

(22:27):

You went this time warmer. I’m sure it was much warmer Alaska, I can’t swim. But that was where women could not become some of these elite things. I mean, everybody had to learn to not drown. But other than that, but also one of the things I got involved in a training program that they were assessing whether or not women could be in some of the non-traditional trades is that again, thinking in terms of women were mostly in the pink trades. And so now all of a sudden they were training people to be like, torpedoman is one of the ones I thought of. And so that transition meant that they were assessing. Actually the way I was involved in it at that time was the actual strength of women in order to do that job. Because in the heat of battle, somebody who’s stronger with, I mean we’re talking long tubes or torpedoes, just like on tv, you can grab ’em with the adrenaline and put ’em in the chute and off they go to kill somebody.

(23:25):

A lot of women do not have the capacity to pick something up like that. I mean, I could not wrap my arms around it. My arms are too short. But they would have a system of wenches that there would be a proper way and safer way to do it. And the question would be, could the job task change? And so there were all of these kinds of going on at the time. And just briefly progressing through my career, I was exo at a reserve center in Charleston. We had 2,500 reservists there, 25 different units of different kinds. And then I was the director of education and training for Naval Telecommunications in Washington. It’s my last duty station. So I really kind of got into the education training and that insight of how do we best people from the needs of the Navy really and to use people to their best capacity. And some of the studies that I was involved in as we looked at changing times, and also keep in mind the internet at that time, very few people were really using technology. When I went to Washington, my secretary had the IBM Electric with carbon coffees. You’re young enough, know what I’m talking about? Carbon coffees. That’s how you made copies

Mary Kate Soliva (24:37):

Machine. And she was still using it.

Amy Stevens (24:40):

Right. And I actually developed an interest in technology when I was in Japan home of technology. I was one of the few people I knew that had a home computer and I actually started taking classes. I knew how to do a little programming, cold ball, fortran, basic dos were the computer languages. At the time when I was working for telecom, I was actually taking people home to see how my computer worked on my home computer. Not because we only had one computer for the office, minimal. It was what they called a green screen. It was very specific the way it was programmed. I cannot

Mary Kate Soliva (25:21):

Even imagine that today like that.

Amy Stevens (25:24):

Yeah, no, I mean it was like the dark ages. Well, the secretary could barely type anyway, but there was a chief warrant officer. We had a little game going on is that he, every night after I left work, he would go and tinker with the computer and kind of break it a little bit. And then the joke was, could I fix it in the morning when I came in? So enhanced my skills. He was smarter than me on some of that stuff. So you’re

Mary Kate Soliva (25:50):

Pioneer. You’re pioneer. Yeah, a little

Amy Stevens (25:52):

Bit. A little bit. And that was actually, that was the time period when all of the RADIOMEN training courses and communications courses for officers in Newport, in Monterey were all shut down because we had to do a complete job cast and realign all of the training to this new thing called the internet. So that was a very interesting time. And by then it was like 19 89, 90. Kind of put that in context for you. So when you think about transition, because I got off,

(26:25):

You can hear some of the stuff I was doing, kind of leading edge technology, all of that kind of stuff, and it was pretty exciting times. At the same time. Another thing that a lot of people may not know about me is that when I was stationed in Charleston as the exo there, I adopted a needs child. And that’s a big part of my story is that my son was 12 years old. He came out of the foster care system. Like many prospective adoptive parents, you get focused on the adoption where you don’t always listen to all the challenges that you might be facing. And my son was definitely a challenge. I won’t go into all of the specifics of it, but it really impacted me personally. And although my son is going to turn 50 this year actually, so I did keep him, he was quite a handful as an adolescent and it really inspired me, an interest in adolescents and psychology and things like that, which I had not done in the Navy.

(27:26):

I was discharged from the Navy. I had a medical discharge, got a degree in counseling actually, I went to Johns Hopkins. And so finishing up my degree, having an acting out teenager at home and I was a single parent. That’s not that uncommon a story probably for a lot of other women that our caregiving for our children is very important that I was trying to get myself lined up to know what I wanted to do. I did go to the Department of Labor, I went to the VA and things were pretty rotary at that time. In fact, at the Department of Labor, I found myself giving spontaneous classes out in the waiting room to people because they did have this kind of a computer, but nobody knew how to use it. And I said, well, if I’m waiting to talk to somebody anyway, I’ll show you how to use the computer so you can help yourself look for a job.

(28:32):

It was like that. Is that because kind of a helper person sometimes. But I didn’t find a good job right away. I mean, I would thought with all my background and of course I did a little career segue into the counseling area. I just did not get the job I thought I would get. And it really took me about five years to stabilize. I did work in the counseling field, I got my degree, worked in the counseling field for a while. I won’t go into all of the background things. And there was the personal stuff going on. My son had some hospitalizations. I had a hospitalization during that time. I think

Mary Kate Soliva (29:08):

It’s important to note about, you said five years. I got off active duty in 21 and I felt like I needed to land on my feet right away, first out the gate. And so that’s where it’s been comforting a few years now after that to see that. I feel like I’m still going through a transition. And there’s a lot of veterans out there that took years to transition. Well, anyone, I didn’t have anybody to help me. They’re calling, right?

Amy Stevens (29:33):

I mean, my family’s up in Maine by then. I was actually living in Maryland, so I had friends of course, but it’s different. They’re not responsible for me. They’re not taking care of me. And I’m a smart girl. You’d think well educated, found some jobs, but I found a lot of the things that I was doing was not particularly

Mary Kate Soliva (29:51):

Even a specialization like you said, even though you didn’t do it while you were on active duty and then you were pivoting careers, which I think is also important to highlight because what you did exactly what you did on active duty isn’t necessarily what you have to do. You don’t have to. And that’s the thing is I was learning about jobs in my job search that I had never even heard of. When you’re a little kid and you’re like, I want to grow up and be a teacher or grow up and be a doctor, and then there’s these jobs that are a specialist, especially even consulting, I found so many veterans and I didn’t even really understand what that meant coming off active duty. So I think it’s incredible with the work that you’re doing now, but I think that that’s something I really want to highlight is that it took you that many years after,

Amy Stevens (30:32):

And it was very, very difficult because I’d gotten into the passion of special needs kids is really what it was. I actually became an activist in the most People now would not know. I’m the founder of the Adoption Therapy Coalition in Washington dc. It’s been drawn into another organization at this point, but there really was no counseling provided for children that coming out of adoption. And my son had a very terrible background of abuse. Remember he was 12 years old when he came to me, the foster care situations and very badly abused and people just didn’t know, especially for boys how to support them. And it also has severe learning disabilities. And I had a passion for that at the time, and I was actually known publicly. I did a lot of speaking on a national level at that time. And of course that’s a long time ago. Nobody knows me now, but I think you’re

Mary Kate Soliva (31:25):

Amazing.

Amy Stevens (31:26):

Did that at the time. And so that was important to me to be passionate about that. And so meanwhile though, especially the medical bills, just tons of medical bills, and this is an important part of this story, is that all of a sudden I realized I didn’t have enough money coming in to make the mortgage. I just really didn’t. And so being proactive, what I actually did was had a couple of potentially good job officers. I was actively seeking work. I was working at a temp agency. Turns out I’m a talented telemarketer. So I mean that’s what I did. I do

Mary Kate Soliva (32:01):

Remember them, the telemarketers still. Yeah,

Amy Stevens (32:03):

I did telemarketing to get regular income coming in, taking care of my son, taking care of my own medical issues when I had emergency surgery. And so I ended up putting my house on the market. I had a really nice sporty car. I turned it into a dealer and got myself a van in case I had to live in it. I sold my house within a week. I didn’t realize I should have asked more money for it. I didn’t lose any money on my house. I made about $20,000 off the house. But I ended up moving in with this lady that I met through my church. I rented a room, so I was paying that, never expecting that I would be there for six months, which is what actually happened. I got myself this thing that was new. Remembering I’m an early adopter of technology. They had come out with these things called bag phones, cell phones, the early version, almost

Mary Kate Soliva (32:57):

Like bag phones. Serious. Yeah. Oh, the big one because it had the antennas. Really all this stuff.

Amy Stevens (33:03):

Yeah. Yeah. It’s like in a history book for you. But no, I got myself a cell phone. I got myself a post office box. I got myself a car that I could sleep in. Keeping in mind also, I had struggled financially a lot when I was in college. So I knew what it was like actually to sleep in my car and not have a place to live permanently. So I had already experienced that and I said, heck no. I’m not going to be sleeping under a bridge. I worked it out for my son to have a safe place.

Mary Kate Soliva (33:31):

What was the job hunt? Was it still, and forgive me, was it like an internet search? Was it newspaper classified ads circling? How did the job hunt go for that?

Amy Stevens (33:43):

Remember the internet was not a thing. And so you

Mary Kate Soliva (33:47):

Go

Amy Stevens (33:47):

To the Department of Labor and they still have, and they’re much better now, but what do they call ’em? DevOps and levers, but basic, that’s acronyms where they have special people assigned working at the Department of Labor to help veterans and that is a good place to go. But at the time, what they had for the computer was a green screen. It was just this little tiny print. And really they kind of do it the same way. You have to go see somebody. You can’t just pull it off the thing yourself. You have to identify,

Mary Kate Soliva (34:20):

Which again goes to the challenge of like, well, how’s the veteran supposed to get there if they don’t have the vehicle?

Amy Stevens (34:27):

The newspaper. The newspaper is what you did. Think about it. That’s what I

Mary Kate Soliva (34:31):

Was thinking.

Amy Stevens (34:31):

The newspaper and professional magazines, if you have, in my case, because I had a specialty, that kind of thing. A lot of it was just through the Washington Post. I can’t remember now where I got my job, but it was like that you really actually mostly used the newspaper. There was not an internet. And again, during that time period, I was taking people home and saying, come see what I’ve got. And we’re talking dial up and people that were executives in their organizations, I was bringing to my house, people from my workplace and we are talking other Navy officers saying, I know we got this thing at work. Come see what I do on my computer at home. And still very, very limited. My son actually got into computers a lot at that time period. And we ended up connecting with some of the early game makers where at the

Mary Kate Soliva (35:27):

Time, that is so cool.

Amy Stevens (35:28):

Yeah, it was very cool. We call up, I’m sorry, I’m not remembering one of them, but it’s a famous one that you would know. The kid was actually working out of his garage and his mom answered the phone. He ended up with this huge company and it is one that you would know, but Richard would actually talk to him on the phone just about all of this stuff. So it was hard to connect. You kind of had to know people, so you’d go to meetings with things, but a lot of it was just somebody you knew and the newspaper and you could go to the Department of Labor, but it was very limited. So it was hard

Mary Kate Soliva (36:02):

To find. And that’s like even with the limited resources, there’s still challenges that transitioning service members are facing today. I know during mine, during the pandemic when things were shut down, it did seem sort of primitive of having to do it the old fashioned way of trying to call up people because there weren’t in-person events and networking and job fairs that were going on in the same way as pre covid. So I’d love to hear about what your advice would be to those who are transitioning now. Any sort of advice, guidance that you’d give to those going through the process?

Amy Stevens (36:34):

Well, number one, don’t give up. The right job is waiting for you. You may have to have a couple in betweens, and that’s okay. I mean, I

Mary Kate Soliva (36:44):

Feel like I’m absorbing this knowledge too. This is quite decision

Amy Stevens (36:50):

Because when you see somebody write their resume and they give you 20 different jobs that they had, my telemarketing jobs are not on my resume. Give me a break. They’re not. But I’ll tell you no, but I will tell you, for a long time I had my secret resume, my special resume, and that was my telemarketer jobs. And it was the one that did not list that I had a master’s degree in counseling. And when they asked if college, I would just say yes. I would not say that I even graduated from college because I needed the job. So I dumbed myself down because I needed the job. By the time I moved here to Georgia, seriously, I had a ton of debt. I was so blessed that I found a job with the US Department of Labor down here in Atlanta. But that took a long time to do, and I still had all of that debt and I had to work my way out of that.

(37:43):

I worked three jobs. Once I got down here, I had my daytime job. That was the full-time job that I moved here for. But I had a nighttime job and a weekend job and the way to get myself out of debt. And no, those people did not know my level of education because it didn’t match. It didn’t really care. So if you’re good at something or you can at least tolerate it to work retail, I mean, that’s the kind of job that really sucks. But the way I was brought up, we were taught to be self-sufficient and social services. What’s that? I think they had food stamps, but I would be embarrassed to ask for that. I know how to eat peanut butter sandwiches and ramen noodles. Right. I

Mary Kate Soliva (38:31):

Had to ask, did you at the time still identify as veteran? Was that something that was brought up? Was there any value to it for employers

Amy Stevens (38:41):

In job funds? Yeah. I’m glad you brought that up. The way that I got my job was because I was a disabled veteran, is that apparently, and it must, and see, the thing is the Maryland department, the state level of Department of Labor actually is probably the way that I got the job down here because they kind of held the jobs in their system. And apparently there had been something, some kind of thing where they had to hire a certain number of veterans, I guess with the US Department of Labor. And so it was very interesting. At the time I went down there, I interviewed in September. I did not get the job. I don’t know what happened, but then I got a sudden phone call in February several months later saying, oh, we want to offer you the job. And it was another veteran and myself that were hired. We were the last veterans that they hired. I worked there for about 10 years. They did not.

Mary Kate Soliva (39:43):

It’s important to note.

Amy Stevens (39:44):

Yeah. Is that apparently there was a checkoff list. I don’t know if there was a lawsuit. I never understood it. All I knew was I got myself a great GS nine job and I moved down here and I’ve stayed here ever since. And I was again getting what that would be. Another thing is get what you came for, figure out how it works. And for me, I had done 11 years on active that I could buy my military years in my federal government job, which I did right from the beginning. I said, how can I make this 11 years count? I did get a separation pay because of the medical discharge, so I got a golden parachute, which helped keep me afloat for quite some time. But okay, can I buy those 11 years? I had heard something about that. So I was able to get that taken out incrementally, not in a lump sum.

(40:32):

So you didn’t really notice it was missing even though I was working those extra jobs. So I got that taken care of. And then what is it take from me to get to the end of the game for retirement? And in my case, I actually took early retirement at age 50. I had a lot of stuff going on. And without going into all the details, I retired at age 50 with a combined 11 years active nine something years with civil service. And so I got a civil service pension at age 50, not a very big one, but it came with health insurance at the time. That was 2004. Very important to have health insurance. Again, you didn’t have social programs that were going to pay for my healthcare. And since I had health problems, I knew I needed to have health insurance, so I would’ve toughed it out longer. I would’ve had to probably work until I was 55 to get a regular one. But they had an early out, they were doing a downsizing or something just like

Mary Kate Soliva (41:27):

I’m glad that you mentioned that about the buyback. That is something I know the veterans getting by the government to do that. But what I wanted to ask about the, because I just be mindful of your time and the time for our talk, but to talk about leading into the organization, why you felt that the need to start the Georgia Military women and some of these things that you’re bringing up now as far as advice, I’m curious if that’s carried over, but would love to segue into that.

Amy Stevens (41:59):

Okay. Well, Georgia Military, an anomaly for sure is I came down here, I finished my career. I ended up, because of the job I took, I did not have to get licensed. And licensure was kind of a new thing for counselors back in the nineties and early 2000. It was just a new thing. So I realized after I retired, I needed to take a break also for some family. My licensure taken care of first when I retired, that was a priority. As soon as I got licensed, then I was able to open a small private practice. And I think that having self-control of my business, we like that flexibility. And I think that’s something a lot of veterans are entrepreneurs. I agree

Mary Kate Soliva (42:42):

With you work

Amy Stevens (42:43):

In a big practice with a whole bunch of other people telling me what to do. And so I did a little budget. I actually did the whole thing like a napkin type of thing, of how much money do I have to to pay my bills? Because by then I had paid off my debts. What can I live on this business? It was very scary to do that. And so I opened a private practice in a little building not far from here that just happened to have a Disabled American veterans chapter having their offices there. And I had really kind of walked away from, I mean, I’ve always been proud of being a veteran, but really not associated with it being discharged rather than retired. I don’t have an ID that could get me onto the local base, and I really wasn’t involved. And because I was there with the guys that kind of hooked me back into it. So that was 2006. And then in 2008, you may not recall, but there was a great economic crash.

Mary Kate Soliva (43:39):

Yes, I do remember that.

Amy Stevens (43:42):

And I was doing relatively well. I was hitting my numbers as far as how much I wanted to make. I had expanded my office. I’d hired a couple people actually to work for me. But when things fell apart, kind of like covid, I guess I realized, oh my God, I better get myself a job that has more steady income. And just happened that the Georgia Department, the Georgia National Guard needed a Director of psychological health and it turned out they wanted somebody that had a doctorate. And by then I had finished my doctorate. So I’m a great believer and things go up and down, but God’s timing is always good. So for me, I had the doctorate at exactly the right time at the right place. And I got the job for three and a half years in a brand new program that they had never had before.

(44:27):

Because previously they would’ve had counselors on active duty, but they didn’t have them for the Garden Reserve. And also, you have to remember at that time, and I’m an old XO of a very, very large reserve. Back in the day, reservists didn’t get called up. They never did. But we know that that changed significantly after nine 11. And so the Garden Reserve are critical members of the force now. And what they realize is that when service members come home that are regular active duty, they’re going back to their bases. But garden reservists are going back to their houses, back to mama or their wife or husband or whatever, and that they weren’t getting resources. And so for three and a half years I did that unique thing. I was the only behavioral health person for the entire Georgia Guard that’s 14,000 people plus their dependent.

(45:21):

So my caseload was very, very large. I will certainly admit to being a victim of compassion fatigue and burnout. It was a very difficult job. We had a lot of fatalities. I attended all the funerals, A lot of people that were wounded. I regularly went to the wts. And there’s some very serious stuff that happened during that time period. But one of the biggest things that I found in it was that once people realized I was there as a contractor and that they could really talk to me privately and I would not tell their business and it would not get into their military,

Mary Kate Soliva (45:54):

I mean that’s so important. That’s the key that won’t get on the record in their command,

Amy Stevens (45:58):

Right at the guard, they wanted me to have office hours and everybody could see who was going in. But my contract did actually, and I learned from this, but basically was supposedly that I was supposed to be available 24 7. And I really was. I had calls all through the night, all through the weekends. That’s how come I got so burnt out. But it was so important, and especially among the women, yes, a smaller component. And we are talking 2009, 2012, that was a time period when military sexual trauma was really coming out to the forefront. There were some very brave women trailblazers that were speaking up publicly and speaking before Congress that before we always knew about it, and sometimes you’d talk about it, but it would all which

Mary Kate Soliva (46:46):

Years was this Amy,

Amy Stevens (46:48):

2009, 2012. That was a pivotal time period. It really was where there was congressional interest in it. And so people were talking about stuff in a different way, and especially the ladies could come in and there were some things going on, which I can’t share here, but I said, number one, I believe you. That’s so important to validate what critical, very critical. And I can tell you one little story is that there was somebody who was assaulted in Afghanistan or a rap, was it? I forget one of those. Anyhow, I’m doing a yellow ribbon event down at Fort Stewart and I would do separate groups for the females because it was infantry units. And I’d ask the girls, I’d say women I should say, because they’re all grown up, but I’d say, do you want to have a formal class or you guys just got back? Would you like to go to Starbucks? I’m buying because it’d be like only five to 10 ladies. Yeah,

Mary Kate Soliva (47:48):

Very small group, right?

Amy Stevens (47:50):

Very small groups. I don’t know. They all picked Starbucks, so it was good. And so I’d have my little bonding moment with them. But one of the things I remember in particular was one young lady actually had been assaulted and she had been sent back to the states and she says, I’ve been back for six months. This is the first time I’ve heard from my unit to report for anything I hadn’t heard from anybody. I said, oh, and we got to talking about the reason why she had been sent back because by then she trusted me and she told me what had happened. It turns out the perpetrator actually was still being held overseas and supposedly big Army couldn’t find her. I said, wait a second. And by then we had a really good SARC sexual assault response coordinator, and I connected her up with that person and that perpetrator was convicted of his crime. The Army jail is in South Carolina. But there were things like that where there were so many gaps and I can’t imagine what it was really like for that young lady to come back after something like that and getting no support, no health treatment.

Mary Kate Soliva (48:57):

No, they weren’t even tracking her. And she didn’t even know

Amy Stevens (49:00):

Tracking her.

Mary Kate Soliva (49:01):

And my goodness, she was just, this is recent years. This is not like you’re talking about 1970. So this is like

Amy Stevens (49:08):

Girl, and she probably,

Mary Kate Soliva (49:09):

Oh, told

Amy Stevens (49:09):

Me if I hadn’t invited the girls to go over to get

Mary Kate Soliva (49:13):

A

Amy Stevens (49:14):

Of coffee, and I remember the little, that’s one of those pivotal things, remembering the little voice in the back of my car, can I talk to you about something that’s private? I said, sure, let’s go over and all this story comes out. And it just really inspired me that I needed to have something. And because of my employment, I really couldn’t do much because there’s rules with the employment and all of that. But once I left the guard, that’s when I started Georgia Military Women, it’s an online Facebook group, is all it is. It is not a nonprofit. There’s no cost to joining it because we don’t have a bank account or nothing like that. It’s just girlfriends that we started with a hundred ladies in the Georgia National Guard, and it’s just become amazing. We have 5,000 members now across the state. It’s very diverse. You just have to identify as a woman, doesn’t matter what branch, doesn’t matter what your discharge status was, any of that kind of stuff. It’s just that you have somebody to talk to. We’re not therapists or caseworkers or financial aid people. It’s really a girlfriend model that you can have somebody to talk to. So we do share a lot of information as ladies are bound to do.

(50:23):

We share a ton of

Mary Kate Soliva (50:24):

Information. I like that little tidbit at the end. Yes, no, but I think that, I love that. And I don’t want listeners to breeze over the fact that you said about it doesn’t matter, discharge status and things like that. Because just like he said, it’s all about support and identifying what those resources are and not feeling like you’re going through things alone because people hit different rock bottoms at different points in their life and you just dunno where people are at. So to have

Amy Stevens (50:53):

All kind of agents,

Mary Kate Soliva (50:56):

Whatever branch it is, sometimes branch, but whatever branch it is, whatever your status was,

Amy Stevens (51:02):

And maybe you didn’t make it through bootcamp, but you raised your hand and you tried and maybe you had an injury in bootcamp, and did you get your benefits for that? Because a lot of times people don’t know about line of duty. Injuries do make you eligible for compensation. And if you were unfortunate to experience military sexual trauma, that is a form of PTSD and there may be compensation available for that as well as if you broke your leg. So it just kind of depends. So often I will find, and older ladies especially have no idea that, hey, if you went to medical, I met one lady who had had a heart attack on active duty. I met her at a job fair and she was an elderly lady looking for a job because she was in financial distress. And we chatted, as I’m apt to do, and she’s telling me about her heart surgery on active duty. I said, well, have you ever filed a VA claim for that? She says, I didn’t think I could.

Mary Kate Soliva (51:59):

Wow.

Amy Stevens (51:59):

And so that was like 30 years prior. She should have been receiving VA compensation for that.

Mary Kate Soliva (52:05):

Even when you mentioned Cold War era, it’s like we don’t have to. I feel like I keep running into so many Cold War veterans that haven’t filed or don’t know what the resources are available to them. So I’d love to see how can our listeners get ahold of you because you have such a wealth of knowledge and information and just you’re also your kind heart and you’re there to listen and you’ll believe. I just would love that. I

Amy Stevens (52:30):

Just like to tell stories.

Mary Kate Soliva (52:31):

Well, the story piece too. I know I can talk. We definitely have to.

Amy Stevens (52:36):

I think that we should always pay for it if we’re blessed. Absolutely. Even if we’re not blessed, the blessings will come. And I think that’s important to have that faith and hope for the future because sometimes adversity comes our way as a way of preparing the way for other things. And if you want to connect with me, I am on LinkedIn, so it’s Amy M. Stevens on LinkedIn and on Facebook, it’s Georgia Military women. I do have a private profile as well that you can follow me there if you want. If live in Georgia and you are female and you are a veteran, we definitely want you to join us and come out and have a time. We just went to a play this weekend at the Alliance. Home Depot is wonderful. They give us free tickets. We like that the Hawks give us free tickets to basketball. You name it, we got it. We know where all the free stuff is, but we just have good time. And it’s about comradery. And I’m always willing too, to help somebody start a program. Again, Georgia military women, it is totally out of pocket, very minimal costs. I hear about all of these big nonprofits and hundreds of thousands of dollars. We got Nada,

Mary Kate Soliva (53:48):

And you’re still making it happen. Amazing.

Amy Stevens (53:50):

And they’ll occasionally reimburse me, but there’s really minimal money involved, and it is kind of a pay as you go. We do cruises and bus trips, and the way that we do it is that it’s at the cost. Nobody’s making money off of anybody, which is amazing that we’re able to do that. But it’s all because we’re girlfriends. We take care of each other.

Mary Kate Soliva (54:10):

I love that. Thank you so much and such a great sisterhood, and it’s an honor to meet you, and I encourage our listeners out there to please share this information, share this episode. Amy, it was such an honor and pleasure. I’d love for anyone to tune in. Again, veteran Voices and as Amy mentioned, to tune in on Facebook and find them, follow or on LinkedIn. So as we always say here on Veteran Voices, you can tune in wherever you get your podcasts from. We are part of the supply chain now family, and as always, do good, pay it forward, especially as Amy said, pay it forward and do the good that’s needed. Thank you all and thank you, Amy, and we will see you all next time. Take care.